I’ve been in Jordan for a few days. I miss polystyrene clamshell breakfast.

Blog

-

Where to eat lunch in the Melbourne CBD

Here’s my very quick reference on where to eat lunch. There’s a very big bias towards the Southern Cross end of the city because that’s where my work is.

-

The taste of test tube meat (an interview with Oron Catts)

(Originally published ‘The taste of test tube meat’, http://www.sbs.com.au/blogarticle/107961/the-taste-of-test-tube-meat [04 June 2008]. I’m republishing it because SBS have taken it down and it gets a shout out in Catts, Oron & Zurr, Ionat. (2013). Disembodied Livestock: The Promise of a Semi-Living Utopia. Parallax. 19. 10.1080/13534645.2013.752062. I think it might have been the first published description of what lab grown meat tasted like(?). Link rot is bad if you’re a researcher. Apologies if you read this more than a decade ago.)

PETA, the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, recently offered a million dollar prize for growing a saleable quantity of artificial chicken in vitro, slabs of meat grown in a laboratory destined for human consumption. The aim: to produce a meat product identical to “real” chicken meat without

any involvement from a free-roaming chicken apart from the unwilling donation of a few starter cells.The New York Times’ knee-jerk reaction was to practically republish the same article the last time something interesting in the world of lab-grown meats came around in 2006. Slate has two of the more insightful articles: one decrying the idea as a poorly conceived prize and economically unviable in the given time frame; the other strangely optimistic. Neither source investigated whether meat from a vat is a taste sensation.

Meat (or at least muscle tissue without veins or bone) has been grown in a lab with varying degrees of success for quite some time but never for commercial sale as food. The process boils down to harvesting and proliferating some original cells (embryonic myoblasts or adult skeletal muscle satellite cells) from the animal of choice, attaching them to a fabric-like scaffold to hold them together and then running a rich and juicy gravy of culture medium over them*. The fabric can be stretched so that the cells arrange into myotubes and then myofibres, making it loosely recognizable as the muscle that would otherwise grow on a more familiar animal.

On the ethical front, eating lab-grown flesh had been given the thumbs up a few years earlier by ethicist Peter Singer:

If, one day, cultured meat becomes an efficient way of producing food, we see no ethical objection to it. Granted the original cells will have come from an animal, but since the cells can continue to divide indefinitely, that one animal could, in theory, produce enough cells to supply the entire world with meat. No animal will suffer in order to provide you with your meal.**

Everything in Peter Singer’s statement is true, apart from the final sentence.

The culture medium that is used to grow artificial meat is made from fetal cattle. If you’re currently growing meat in a lab, you’re essentially making meat with other meat, reducing a larger animal into a miniscule sliver of flesh. You’ll need an obscene number of fetal cows to produce a saleable amount of meat because the process is about as efficient as raising a chicken, eating a single but perfectly-formed feather and then throwing the rest of the bird away.

If PETA (or Peter) had delved into the Journal of Tissue Engineering, I’m sure that they’d be mortified to know that hundreds (if not thousands) of litres of liquefied cow would be needed to produce a kilo of meat using current techniques. No vegetable or mineral replacement for the calf serum looks at all promising. The utopian vision of having a bread machine-sized bioreactor in every home, generating aged porterhouse on command, does not look as tempting to the vegan set if you have to pour a drum of calf extract into it to kick start the process. It doesn’t look hugely attractive to a committed carnivore either.

Obviously the current techniques aren’t aimed at the estimable vegan ethicist or even the most amoral bacontarian; they are harnessed for the more important task of growing human body parts for human transplantation, an ethical minefield when we start to weigh the value of human lives against those of animals. But beyond the question of ethics (and more relevant to this food blog), how does vat-grown meat taste? And why is taste so rarely central to these debates?

The most hopeful of the lab meat farmers namely, Jason Metheny from Soylent-Greenish-sounding New Harvest, hopes that the first few vat grown products to hit the shelves will be “traditionally processed meats as hamburger, sausage,chicken nuggets or fish sticks” which hardly sets the bar too high in terms of tastiness and suggests that the man has never eaten a truly great sausage nor considered that all these products already function to turn meat waste into tasty treats.

There are eight people on earth who have already eaten lab-grown flesh, and artist and tissue scientist Oron Catts at the University of Western Australia is one of those few. As part of the Tissue Culture and Art Project’s Disembodied Cuisine, he was part of the team that grew some frog meat on a slide, fried it up and ate it as a part of a “feast” to end their project into the uneasy relationship of meat and science. Following earlier successes in 2001 at growing lamb in a lab, Catts and his team grew coin-sized frog steak in 2003 at a cost of roughly $650 a gram, just millimeters thick.

“We grew the frog meat on a matrix which was like fabric and didn’t exercise the muscles,” Catts says. To grow like a living muscle, the matrix needs to be stretched. At the end of the two and a half month exhibition, the matrix had not fully broken down and remained quite intact.

They fried the thumbnails of frogmeat in garlic and honey with a dash of Calvados, a recipe which they named “a la Davis” in honour of a fellow bio-artist Joe Davis whose frog muscle-powered ornithopter failed to launch on ethical grounds, a process as cruel as marinating dead amphibian in honey and eating it.

The Lilliputian amphibian steaks were served with a selection of herbs, also lab-grown from plant tissue culture. Eight people sat down to this micro-degustation. The results were a success, at least in terms of replicating an uneasy relationship.

“Four people spat it out. I was very pleased”

As for the sensation of eating lab-grown meat: “It tasted like jelly on fabric.”

* – It is of course, much more complex than that to grow meat in a lab and it’s also not gravy, it’s liquified fetal cow parts. There are a few different tactics to growing muscular tissue. If you want a summary of growing meat in a laboratory, read “In Vitro-Cultured Meat Production” P.D. Edelman, M.Sc., D.C. MC Farland, Ph.D., V.A. Mironov, Ph.D., M.D., and J.G. Matheny, M.P.H., TISSUE ENGINEERING, Volume 11, Number 5/6, 2005. Then you can complain about the huge amount of science that I summarized into a single blithe paragraph.

** – Peter Singer and Jim Mason, The Ethics of What We Eat, text publishing, 2006, p.237

-

Great carbs of the Western Suburbs: Pandesal

The history of the colonisation of Asia is written in its bread. Pandesal, the national breakfast bread of the Philippines, was borne of Spanish colonial rule but processed by the USA. The bread came from the more Spanish pan de suelo, crusty “bread of the floor” cooked on the clay base of the oven from the 1600s, but as M. Paramita Lin writes:

Pan de suelo is likely the precursor to pandesal, which didn’t come about until the American colonial era; Americans objected to eating bread cooked on the oven floors and thus pandesal, baked on metal trays, was born. But even then, it didn’t look like the rolls that are sold now. (Food historian) Sta. Maria quoted Alice Fuller, who wrote Housekeeping: a Textbook for Girls in Public Intermediate Schools in the Philippines, writing in 1911 that pandesal was “[a] small oval-shaped loaf of bread very common in the Philippines. Prepared much the same as ordinary bread, but baked much harder. The loaf, when baked, is 9 to 15 centimeters long, 7 to 9 centimeters wide, and about 4 to 6 centimeters thick. Prior to baking the loaf is gashed longitudinally on top so that the baked loaf may be easily broken into halves.”

Over time, pandesal has moved from a loaf to a smaller, sweeter bun but more than 90% of the Philippines milling wheat imports still come from its more recent colonizer, the USA.

Outside of the western suburbs, there aren’t many other Filipino panaderia in Melbourne. There are two in Braybrook (Masarap and just around the corner, Papabear Bakehouse) and one in St Albans, (Manila’s Bread Bakery). Papabear is better for Filipino sweets and cakes, Masarap which has been in the small Churchill St shopping strip for about 20 years is more focused on yeasty provisions which they sell from the shopfront and distribute to other grocers around Melbourne.

Masarap is Tagalog for delicious. Their pandesal is delicious. They sell enough of it that it is warm whenever you get there, and generally, never on display in the front. The outside of the buns is rolled in breadcrumbs, a reminder that pandesal cannot exist without bread already existing before, inside is pillowy. It’s a sweet-savoury carb hit.

Masarap Bakery

178 Churchill Ave, Braybrook VIC 3019 -

Soyfoo Anh Long, Braybrook

Soyfoo Anh Long is a tofu shop on the vertiginous northern edge of Braybrook that drops into the Maribyrnong river valley, amongst the wrecking yards that advertise on hastily scrawled “Cash For Cars” signs stapled to a power pole. Their precast concrete panel factory was once neighboured by a business called “Hair Extension Online” who never seemed to be open to extend hair or have ever been in any way online.

This is the ne plus ultra of Melbourne Western suburbs food locations, if you ever want to weaponize a flawed sense of authenticity. Or you could just order it on doordash, like normal people. Treating anywhere like a “hidden treasure” ignores the economic reality of running a food business: cheap factory space will always be in the margins. You can find it by googling “soy near me”.

I ride my bike past it most days. It’s the end of the 20km loop that I ride than ends at the Lacy Street wall; a series of 11% gradient switchbacks that wind out of Cranwell Park. I try to climb it fast enough that I can’t talk afterwards. I roll past Soyfoo Anh Long in no state to eat tofu. I took today off.

They make: firm tofu (plain, fried in different convenient cuts, mushroom and vermicelli, lemongrass and chilli), soy milk and tau foo fah/đậu hũ đường, the refreshing silken tofu pudding dressed in a simple ginger syrup (above). The shop also fills its fridges with mock meats, has a selection of dry Vietnamese noodles and primarily vegetarian sauces.

The biggest payoff of getting to the factory in person is freshness. The fried mushroom and vermicelli tofu is warm from the fryer whenever you arrive, the strips of black wood ear fungus and noodle in it are the best textural counterpoint to the crispy exterior. You can just eat it straight or toss through sichuan pepper, salt and chili when you get home for more of a kick.

Location

Soyfoo Anh Long

24 Cranwell St

Braybrook VIC

Tofu is also stocked at many western suburbs grocers. -

How Google Recipe Search ruins food: hoisin sauce edition.

Because I’m a food idiot, I like making sauces from scratch. Why not hoisin sauce? With a general knowledge of what’s in hoisin sauce (it’s soybean paste-based and has historically followed Cantonese migrants around South East Asia), I Googled “hoisin sauce recipe”.

Here’s what was served up: 6 out of 9 based on peanut butter, one based on black bean paste, 2 with a soybean paste base.

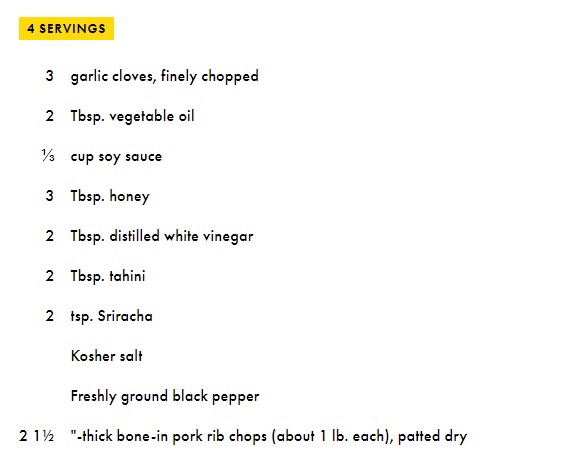

A special mention/middle finger to Bon Appetit, because here’s their hoisin horrorshow which seems to define hoisin sauce as something vaguely brown and ahistoric. White supremacist food is putting sriracha in something and calling it by whatever Asian name you feel like.

If you didn’t know what you were doing in advance and had never read the ingredients on your bottle of Lee Kum Kee, you’d assume from Google that hoisin sauce was a sweetened, lightly spiced peanut butter. In recipes, good SEO beats food knowledge and Google has set up a perverse incentive for big sites to write bad recipes. If you want a site to be on the first page of Google for “hoisin sauce recipe” you’re probably going to look at the top five existing recipes and copy them rather than questioning whether any of them are good. As Google builds “better” machine intelligence and semantic search, it will assume hoisin sauce is made from peanut butter, because most of the websites say it is, even “reputable” ones like BBC or Bon Appetit.

It becomes a virtuous cycle of shit.

Maybe Anglo hoisin (spiced peanut butter) is metastasizing into different sauce from Cantonese hoisin (sweetened soybean paste) and Vietnamese hoisin/tương đen (sweetened soybean paste with MSG and caramel color (150c)) and Google reflects both semantic drift between languages and changing national tastes. Cookbook author and blogger Andrea Nguyen made the observation in 2010: that tương đen/tương an phở and Cantonese hoisin are clearly different sauces, even when they’re made by the same manufacturer (Lee Kum Kee) for presumably, the same market.

Lee Kum Kee, probably the world’s biggest manufacturer of hoisin, says the origins of the sauce are Hakka (Kaixuan sauce?/”凯旋酱”?) rather than Cantonese, so it is probably a sauce with a lot of genocidal history to unpack.