Author Archives →

Selling raw human misery to Quincy Jones

Originally sent: 22 November 2005.

My bizarre marketing task for the month has been deciding how to suitably horrify Quincy Jones.

For those of you playing at home, Quincy Jones is the all-time most nominated Grammy artist with a total of 77 nominations and 27 winning Grammys. He has won an Emmy and seven Oscars. He’s the man who wrote the Austin Powers Theme, made Will Smith famous on The Fresh Prince of Bel Air, and composed the world’s funkiest organ-driven title track for “They call me Mr. TIBBS!”. To top this off, he’s one of the few jazz musicians that I like from the bebop era that didn’t burn down their career in a blaze of heroin addiction. At the behest of UNICEF, SCC are taking him to experience as much raw human misery as he can stomach for two and a half hours to try and take a percentage of the profits that he made selling a hundred million Michael Jackson albums and Lesley Gore’s 1963 teen hit, “It’s My Party”.

The initial meeting with UNICEF to plan Quincy’s visit was strange in the extreme, partly because I was the only marketing person there and saw this purely as a sales exercise, partly because the whole group of us had become so inured to the suffering that we can use it comfortably as a marketing tool. Head UNICEF guy wanted us to show the visiting party a “range of Cambodian families” which after much discussion was decided that UNICEF wants us to display:

1) A family headed by someone with AIDS, dying in a dirt-floor shack;

2) A family where person from 1) has died, but family still supported;

3) A child-headed household/kids with AIDS.

We allotted 30 minutes per family.

I have a much more cynical trick up my sleeve because I’m the only person that knows who Quincy Jones is – and I like that marketing is a dirty sport. A few of the orphans and vulnerable children (known in the aid business as “OVC”) are learning Khmer traditional music at SCC’s pagoda in Siem Reap. When we throw some monks into the mix, surely that will make Quincy bleed cash.

As instant karmic penance for doing aid industry dirty work on behalf of monks, the next day I got hit by a Landcruiser while I was riding my bike on the way to the office. It’s much less serious than it sounds. I was stationary at a crossroads and the Landcruiser hit me from behind while it was trying to barge its way around the corner. I’m thankful that they didn’t stop and either try to extort some cash from me or shoot me for denting their car. I obviously look like the sort of person who can afford to buy whatever sort of retributive Cambodian justice I feel like.

M’s parents were here for three weeks: in between working, we did all the Cambodian provinces which aren’t too scary, too wet, or too poor to have anything at all in them. To fit in our travels, there are 6 public holidays in November: 3 consecutive days for Water Festival, 2 for Independence Day, 1 for the old King’s Birthday (Hail, Sihanouk!). By juggling my leave the right way, this month I will spend 8 days at work.

About a million Cambodians from the rural provinces come to Phnom Penh for Water Festival to pickpocket the rich white folk and serve as the butt of rural/urban divide humour. They were all at the Phnom Penh’s only mall when I went there, to see escalators and air-con for the first time. About half of the kids would jump on the escalator before their parent, so the parent – bewildered by the foreign mechanical stairs – would hold on to them. This resulted in momentum knocking them over and the oncoming stairs thoroughly shredding the children, while the Phnom Penh locals would revel in rural/urban divide humour that watching kids fall into a meat grinder creates. The vein of Cambodian physical comedy runs deep.

We missed everything for which the festival was famous: live appearances by the new King (Hail, Sihamoni!); dragon boat racing and the associated drownings; a million rural people using Hun Sen Park as a urinal. Instead we caught a taxi to Kampot, which has a rotting colonial cliff-top casino ghost town (Bokor); and Kep, which has the tastiest seafood in all Cambodia.

Bokor was where the French elite went to acclimatise to Indochina before the locals formed their own substitute for European colonial rule, and as they did with anything on a hill in Cambodia, turned it into a gun emplacement. Building Bokor casino would have had the same degree of difficulty as building a quaint French village by hand on top of one of the 12 Apostles using only an infinite amount of disposable Cambodian labour. Judging by the leftovers, beachside colonialism looked like it was a whole lot more fun and profitable than my postcolonial development junket.

Street food isn’t a cuisine: it’s food that happens to be outside

Just because you barbecued that tongue next to a road doesn’t make it a cuisine

I didn’t attend the World Street Food Congress a fortnight ago in Singapore but the outcomes from it seem to have devolved into the basest discussion of street food: name-calling, jingoism and fear of foreigners at once romanticising and ruining otherwise “authentic” food cultures. Some foreigners points of view seemed to be valid simply because they get parachuted into a cuisine courtesy of a television show, others invalidated despite decades of experience in the field and most likely, being the fixers for those same television shows. While I wasn’t at the conference, I’m no stranger to being accused of both creating nostalgia for and wrecking street food for foreigners and locals alike.

Singapore is a strange place to hold a street food conference given that most of its street food has been moved to malls and hawker centres. Conference founder KF Seetoh conflates the two. Bon Appetit’s Jenny Miller, covering the conference interviews him:

. “Street food is a cuisine, not a physicality,” he insisted. When I approached him after a panel to press the question, “Isn’t something lost when you move street food off the streets?,” he seemed impatient: “You are romanticizing it. Do you want to get food poisoning?”

Street food isn’t a cuisine: it’s food that happens to be outside. Food that is served on the street is a subset of the wider regional cuisine. The elements that link street foods together across different cuisines and cultures have little to with the food itself and more to do with local conditions that drive vendors into the outdoors. Mostly, that condition is poverty and lack of regulation which adds an awful irony to a conference that costs $750 in a nation ridiculed for its regulations. Additionally, there is a body of research demonstrating that the risk of street food contamination is low and not any higher than in restaurants.

What is lost when a street food moves indoors is transparency. When the food is served outside, you have an often far too intimate and transparent relationship with the food preparation. One of my favourite stories of this intimacy is from Austin Bush, eating the Burmese pickled tea leaf salad, lephet thoke:

Once several years ago I ordered the dish at a street stall in downtown Yangon. The woman mixed the dish, in the traditional manner, with her bare hand, squeezing and squelching the mixture thoroughly. After serving me the lephet thoke, she then stared at me while I ate it, licking her fingers the entire time.

On the street, there is generally nothing to hide: you can immediately pick a popular stall from an unpopular one, you can eyeball the chef, see the ingredients and preparation. In a mall, this doesn’t happen. So what’s the value in rolling together food that is served on the street and food from the mall?

My guess: billions of tourism dollars. Food tourism is gigantic business. In 2003, Tourism Queensland estimated that 22% of international visitor expenditure is food. If this held true for Singapore, whose GDP is ~10% tourism, this would be worth SGD$7.7 billion. The international fight to be perceived as having the world’s best street food is a high stakes game.

Faux Pho

Originally sent: 10 October 2005

Pchum Ben, a holiday to appease the spirits of the dead, happened last week. Most Cambodians leave Phnom Penh to give offerings of food at their local pagoda to ensure that their deceased relatives don’t return from the grave to stalk the earth as a hungry legion of the Undead. I’ve been told that there is a type of ghost that can take possession of you while you sleep and detach your head and innards from your body, and then float about using your entrails to consume unsuspecting victims and livestock. Pagoda offerings apparently sate their bloodlust for the year.

The good news for non-believers is that firstly I get 3 consecutive public holidays, so could get a boat down the Mekong to Vietnam to avoid the local undead; secondly that the Buddhist monks get to eat their fill of the offerings and then bring the leftovers to work for me. On a good day, I get banana-leaf packages of sticky rice that surrounds a delicious banana/bean filling and on a bad day, I get banana-leaf packages of sticky rice that surrounds a fatal raw fish/salmonella filling. Both are identical from the outside and their true nature is hidden by the odor-masking properties of banana leaf. Picking the wrong one feels like your stomach has been taken on a entrail-detachment joyride by a poltergeist.

Partly due to the expense of flying anywhere, we decided to sail to Ho Chi Minh City. For $20 we were promised a bus then boat straight into the Mekong Delta bird-flu territory, a night’s accommodation, tours, then a bus to Ho Chi Minh City. My workmates thought that for that price we were being sold into slavery. We were also promised that we could get our Vietnamese visa in 24 hours which I still can’t believe happened.

The boat to Vietnam was fairly uneventful. Kha Orm Nor at the Cambodian border has the silliest border post I’ve seen, insofar as it is the only one I’ve seen with an Olympic-quality badminton court. When the boat arrived there, M thought that we were stopping at a riverside resort for lunch; the Cambodian immigration guys had a level of joviality that could have only been brought on by an excessive amount of either badminton or extortion. They laughed so hard when I spoke some Khmer to them that they didn’t even bother looking at my passport before stamping me out of Cambodia. Just down river, the town of Chau Doc is the preferred launching port for petrol smuggling into Cambodia and so the border guards must be getting their fair piece of the action. Vietnam subsidises their fuel, Cambodia doesn’t, and so a canny Khmer smuggler can make as much as $1 a day in arbitrage depending on how quickly they can row.

Chau Doc has all the ambiance of a 15th century smuggling port and thankfully we were only staying for a night and far enough from town to not be conscripted into a life of river piracy. Near the hotel was Sam Mountain, which was predictably spruced up with shrines to practically every faith; unpredictably it was covered with giant concrete dinosaurs and mermaids, possibly presaging a return to animism for Vietnam. The next morning, we got our dose of authenticity by having someone canoe us about the Mekong so that we could point our cameras at unwary floating fish farms, pagodas, and the local Cham Muslim people.

Apart from doing the sights of old Saigon, the real highlight of getting to Ho Chi Minh City was eating vast quantities of Vietnamese food which we could then wash down with the local coffee. One of the weirdest things I’ve been missing from Melbourne is Vietnamese noodle soup (pho) from Mekong Restaurant on Swanston Street; a desire made even stranger because there is a Vietnamese restaurant about 5 minutes away from our house in Phnom Penh to which I have never been. As an indicator of how much we ate, the only piece of Vietnamese language I learnt was “pho” which is actually pronounced more like “fur” than “poe”. I also make guest appearances as the wanker that orders in French. Very little of the pho lived up to Mekong’s extremely high standard, even though most of our two days in HCMC was spent wandering about trying literally every restaurant and cafe we saw.

The only place we actively sought out was a restaurant that specialised in barbecue that one writer has described as “filthy top-shelf meatporn“. Animal genitalia was a dining option, along with the usual array of rodents, reptiles, arachnids, and Bo Tung Xeo after which the restaurant is named: marinated beef chunks that you lightly sear on your own white-hot table top barbecue. After inspection of the live snakes, we opted for the beef with a side serve of goat flesh. It was so juicy and tender that my next purchase in Phnom Penh will be deworming tablets.

M judged our bus ride home as the worst that she has ever been on, and she’s been on a bus ride on the road that is legendary as the worst in the world (La Paz to Rurrenabaque, Bolivia). The last 60km from Neak Luong to Phnom Penh took about ten hours to cover, seven of which were spent queuing for a ferry. We would have been slightly better off swimming the river, buying an ox cart to drive us home and then barbecuing our means of transport as a Pchum Ben sacrifice. The bus was made all the more excruciating because the travel agent we’d booked through in Vietnam lied and didn’t book us seats, so we got one seat and one plastic chair in the aisle. M managed to strongarm her way into a seat when the previous occupant got up to have a vomit. It got that nasty.

Other than our weekend travels, I’ve been doing feelgood, humanitarian work that you see in UNICEF think-of-the-starving-children brochures: distributing schoolbooks to children with AIDS. It is more depressing than rewarding as many of the kids or their families will be dead before the school year ends, although I did get a superb moment of ecumenical irony when I realised that we were using Buddhist monks to distribute cash from a gay Christian church to Muslim school children. It is annoying that it is so easy to find money for these sort of projects rather than finding money to pay our accountant a decent salary, so that more of these sort of projects are possible in the first place.

Addendum: 2012

After I sent this group email, a few of my friends emailed me back to say that I should publish them because they had started forwarding them on to their friends.

I’d been kicking around the idea of starting a food blog for a few months but after their emails I registered the URL phnomenon.com, named after the subject line of the first group email that I sent.

Finding posts near the user using Geo Mashup

If you’re not someone using WordPress, this post is not going to be of any interest.

Brian over at Fitzroyalty asks whether it’s possible to order content on a blog relative to reader’s location. It is. Here’s how, or at least here’s how to add a button to the sidebar/menu on a WordPress blog that:

- Detects a user’s location

- Finds a list of posts that is closest to the user’s mobile location using the Geo Mashup plugin

I know that this is a terrible hack to get something done quickly. I’m not much of a coder and I’m sure that there is a better way to get this done using Geo Mashup, but as far as I can find, nobody else has done this before.

Here’s how to do it.

1. Get the Geo Mashup plugin, enable and geotag your posts.

2. Get a PHP plugin that lets you execute PHP in posts and enable it. (You could of course, write your own custom template and put the PHP straight in, but as I said, this is a quick fix).

3. Go to Pages > Add New and add a new page. All you need on it is:

[geo_mashup_nearby_list near_lat="<?php echo ($_GET["near_lat"]); ?>" near_lng="<?php echo ($_GET["near_lng"]); ?>" limit=10]

4. Name the page whatever you like and save it. It won’t work yet. Copy down the URL.

5. Go to Appearance > Widgets. Add a Text widget to your menu wherever you want the “Find Posts Near Me” button to appear.

6. Give it a snappy title like “Nearby”, then in the text box add this code:

<script src="http://www.YOURWEBSITE.com/wp-includes/js/jquery/jquery.js"></script>

<script type="text/javascript">

jQuery(window).ready(function(){

jQuery("#btnInit").click(initiate_geolocation);

});

function initiate_geolocation() {

navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition(handle_geolocation_query,handle_errors);

}

function handle_errors(error)

{

switch(error.code)

{

case error.PERMISSION_DENIED: alert("user did not share geolocation data");

break;

case error.POSITION_UNAVAILABLE: alert("could not detect current position");

break;

case error.TIMEOUT: alert("retrieving position timed out");

break;

default: alert("unknown error");

break;

}

}

function handle_geolocation_query(position){window.location ="http://www.YOURWEBSITE.com/LOCATIONPAGE/?near_lat=" + position.coords.latitude + "&near_lng=" + position.coords.longitude;

}

</script>

</head>

<body>

<div>

<button id="btnInit" >Find my location</button>

</div>

Replacing “www.YOURWEBSITE.com” with your URL and http://www.YOURWEBSITE.com/LOCATIONPAGE/ with the location page you made in step 3.

7. Press “Save” to publish the widget.

8. Enjoy! In theory, if anyone has a browser that runs HTML5 (pretty much every modern browser) when the button is pressed it will read the user’s location, ask for permission to use it, and then send that to the map page, listing the posts nearby in order of distance (as the crow flies). This doesn’t store the location anywhere.

Feel free to use/improve this code. If I was a better coder, I’d build it into a plugin. Don’t contact me for any suggestions to add to this. I have no idea what I’m doing.

Keeping it Riel

Originally sent: 23 August 2005

M and I recently has four day weekend in Bangkok which was great for all the wrong reasons: my personal highlights were going to the movies; eating Mexican food, smallgoods, and two and half pork-fuelled hours of yum-cha; and staying in a carpeted room. M picked the hotel because it was the home of Thailand’s best Mexican restaurant, Señor Pico’s of Los Angeles. The good Señor did not disappoint, and as you can see, we’re becoming the very picture of jaded expats. We even started marvelling about how clean and beggar free Bangkok is, which was a stark reminder that we’ve been living in the world’s fifteenth poorest nation for quite a while.

As for the authentic Thai tourist experience, we’ve already torn the Grand Palace, Emerald Buddha, Huge Reclining Buddha, and Chatuchak Market pages out of our pirated Lonely Planet. They’re the same as Cambodian attractions only ten times larger and made from solid gold rather than chicken wire over bamboo.

My adventures with the monkhood have continued to reach new levels of surrealness. SCC’s three monk leaders sang me “Happy Birthday” in English when I came to work on the morning of my birthday. They even had the words almost correct, they sang:

Happy Birthday to you

Happy Birthday to me

Happy Birthday to you

Happy Birthday to Mr Phil

I have discovered that the reason that monks are the essence of serenity is that they’re taught to meditate while walking slowly and serenely. If they don’t walk serenely enough while they’re at their pagoda, they get beaten with a length of bamboo by an older, more serene monk, which is allegedly the way of both Theravada Buddhism and cheap kung-fu films.

I also had my best interaction with a monk so far: he’s in his 40s (which is rare for a monk, as the Khmer Rouge did their best to chop up the guys in robes) and I asked him what he did before he was a monk. He said he was a miner until he was 15 when he joined the monkhood. I asked what he mined for (there are a few sapphire mines around town and some marble quarries). He said: “I mined for tanks, trucks and sometimes people, but not trains.”

Previously in this series: They can’t drink the alcohol or woo the ladies

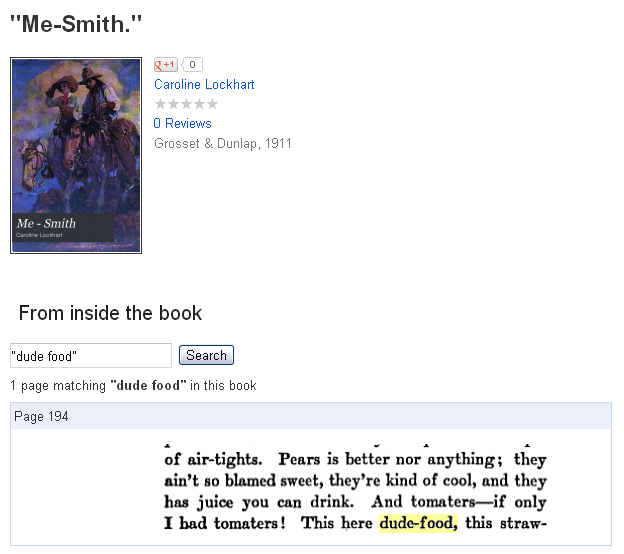

First mention of Dude Food? 1911

I’ve been searching around a little for the etymology of the term “dude food”. Even though its use seem to blossom in the late 80s, it seems to have been around for a long time, referring to cowboys. The earliest that I can find is from journalist and author Caroline Lockhart’s first novel in 1911, Me SmithFrom Google Book Search