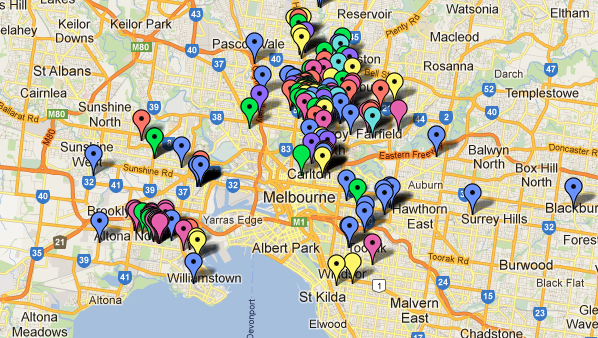

Three hats

Attica, Jacques Reymond, Royal Mail Hotel, Vue de Monde.

Two hats

Cafe Di Stasio, Cutler & Co, Ezard, Flower Drum, Lake House, Loam, Matteo’s, MoVida, The Press Club, Provenance, Rockpool Bar & Grill, Stokehouse, Stefano’s, Tea Rooms of Yarck, Ten Minutes by Tractor.

One hat

Albert St Food & Wine, Bacash, Becco, Bistro Guillaume, Bistro Vue, Cecconi’s Cantina, Church St Enoteca, Circa, Coda, Cumulus Inc, Dandelion, Donovans, Easy Tiger, Embrasse, Estelle Bar & Kitchen, European, Eleonore’s, Gills Diner, Gladioli, Golden Fields, The Grand, Grossi Florentino, Il Bacaro, The Italian, Kenzan, Koots Salle a Manger, Longrain, Maha, Mercer’s, Moon Under Water, MoVida Aqui, Paladarr, Pei Modern, PM24, The Point Albert Park, Sarti, Shoya, Spice Temple, Steer Bar & Grill, Tempura Hajime, Town Hall Hotel, Yu-U, A la Grecque, Annie Smithers’ Bistrot, Bella Vedere, Chris’s Restaurant, La Petanque, The Long Table, Montalto, Neilsons, The River Grill, Scorched, Sunnybrae, Teller, Terminus at Flinders Hotel, Villa Gusto.